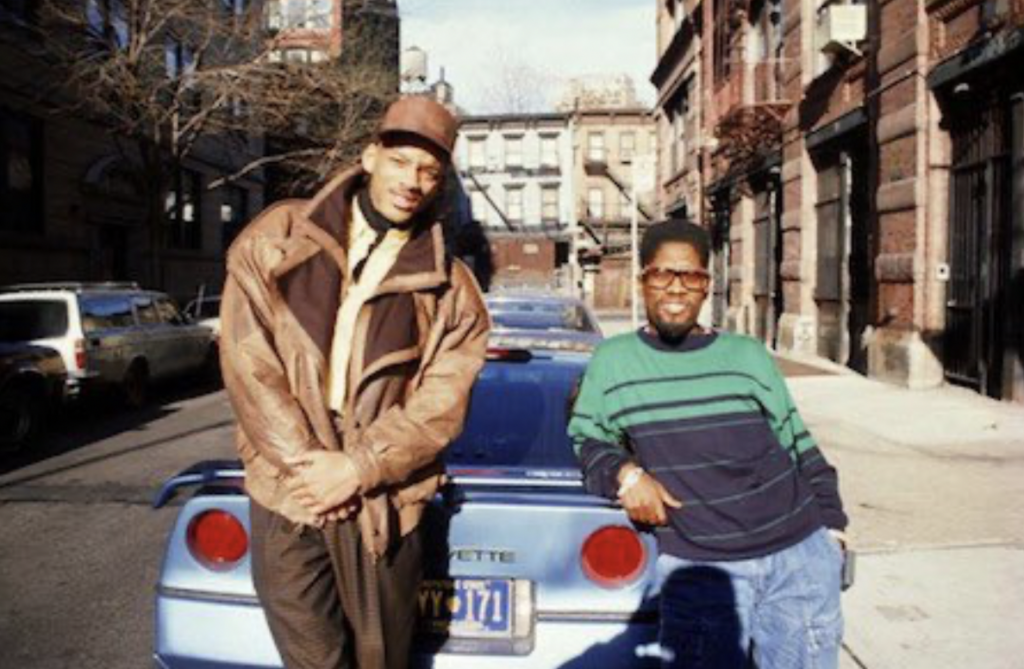

Kervin Simms – that name might not ring a bell, but some of his clients just might. Like many in the neighborhood, Kervin radiates an understated, low-profile cool. These days, he works as a lawyer and contract specialist, representing legendary musicians, writers, filmmakers, actors, Estates of noted Artists, and others in the entertainment industry. Though he isn’t usually the one in the spotlight himself, he’s been right here in NoHo living and working behind the scenes for some of Hip-Hop, R&B, Jazz, and Soul’s most legendary acts. In celebration of Hip-Hop’s 50th anniversary, we’re looking back on the Golden Age of Hip-Hop here in NoHo with a man deeply enmeshed within the scene itself.

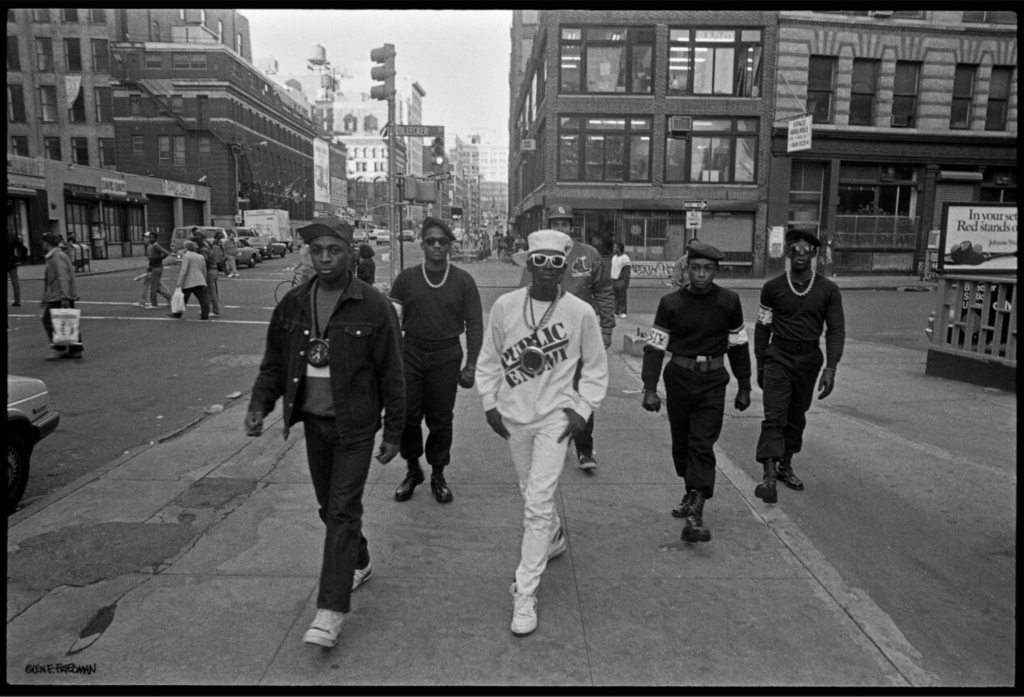

The Golden Age of Hip-Hop, roughly the mid 80s to late 90s, was a dynamic period here in NoHo, with many of the eras most iconic, larger than life players like Rick Rubin and Russell Simmons entering the spotlight from our neighborhood. The genre went from an outer borough phenomenon to one centered around a booming scene Downtown, including here in NoHo. Fueled by the concurrent rise of NYC’s legendary club scene in the 80s and 90s, hip hop found a home in lower Manhattan among effortlessly cool restaurants, stores at the cutting edge of fashion, and of course cheap commercial space to launch a career. Long-gone clubs and venues like The Bottom Line, Blue Willow, Time Café (Fez), Table 50, Sticky Mike’s Frog Bar, The Tin Palace, The Village Café, and so many more welcomed all kinds of genres, and were vitally important to the development of the hip hop scene in NYC in the 80s. From there, it kept building steam, and before long hip hop had become enmeshed in the creative set downtown. Moreover, the Downtown arts scene not only embraced hip-hop as a legitimate counter cultural arts movement, but welcomed it along with its visual contemporary, graffiti. As Kervin puts it, “it was just the place to be. Everybody wanted to be down here where the action was.”

After a stint at the District Attorney’s Office, Kervin decided to go out on his own as a young lawyer. Originally, his office was located uptown in Harlem, however, back then “there weren’t enough full service restaurants around, that I could entertain clients for breakfast, lunch, dinner nearby.” Kervin found himself constantly taking a cab to NoHo to visit the city’s most exciting, new restaurants that everybody, including his clients, wanted to go to. Hit new spots like The Odeon, Bardo, Bayamos, Indochine, NoHo Star, and of course, the legendary Time Cafe. By the time he shuttled himself back and forth five to six times a week, Kervin was spending so much money in cab fare that it made sense to move his office here. He’s been living and working in NoHo for thirty years since.

NoHo in the mid-90s was a dynamic, creative place, and when he moved his office on Broadway the next year, he found himself sandwiched between industrial uses, recording studios, artists, and a dance studio that constantly brought in loud congo drums. “It was all creative. There were also a ton of recording studios.” While the big record labels were centered around Midtown because of cheap commercial space, NoHo and the rest of lower Manhattan was the hub for small, upstart labels and where many of the exciting new young recording artists, music producers, management companies, publicity and marketing firms found a home. Kervin fondly recalls emerging superstars, including Teddy Riley and the genre he created, New Jack Swing, hosting recording session performances and shows right in his recording studio on the 5th floor of 636 Broadway.

Everybody who was anybody in the entertainment world wanted to be here. To say it was the place to see and be seen was an understatement. Kervin fondly looks back on late nights spent at the legendary Greene Street Café, Danceteria, Save the Robot, The Knitting Factory, and also spending time amongst the chic eateries that had popped up all around here. He recalls that this area was filled with constant excitement, and an unmistakable energy that ran along Broadway from 8th Street all the way to Canal Street.

Around this time in the early 90s, major record labels began snatching up rising hip-hop talent in New York City, and there was a major infusion of money. The influx of cash from major labels allowed all these youthful entrepreneurs to set up shop where they wanted, and they wanted to be here. By the time hip hop began to explode, NoHo was known as a hub of artistic activity, which included the visual artists, film, and theater. This area was already the place to be for many artists, and suddenly the upstart hip hop movement had the funds to stake their claim on a slice of lower Manhattan. The more established fine arts scene also welcomed hip hop into the fold, and another layer of creative activity was added into the artistic tapestry of NoHo. With hip-hop already firmly enmeshed in the NoHo scene at this point, this stream of funding helped further establish itself as a driving force in NYC. Def Jam Records, Rush Management, Gee Street Records, Chung King Studios, and many other legendary hip hop institutions called NoHo home, but lost to time is the small, diverse collection of studios that filled the upper floors of Broadway and Lafayette Street. Back then, it was a who’s who in NoHo hotspots, and our neighborhood was the place where deals were constantly consummated.

Though everybody remembers Tower Records, the upstairs of buildings here were lined with independent labels and production companies. He remembers some of the young Tower Records employees eventually becoming major A&R executives of the major labels. There was a hustle and bustle to NoHo then, with a constant stream of artists, writers, recording studios, fresh label executives, and many others constantly wheeling and dealing. With a laugh, Kervin recounts as a young upstart entertainment lawyer, a story of the time a neighborhood character, Mike, helped him successfully navigate a contract negotiation. Kervin, who was still learning the contract game, was leading negotiations for a client, when Mike found another company’s contract in the trash and gave it to him. The contract put Kervin in the perfect position to leverage a deal. Eccentric folks like Mike were everywhere in NoHo back then, and Mike himself had been living on the streets of NoHo for decades, and knew just about everyone and everything about the neighborhood. He would tell Kervin all about neighborhood history every time he had the chance, like when Billie Holliday lived on Crosby Street and the Bowery Boys ran the neighborhood.

One of the most important things to come out of this time, however, was the opportunities it created for many young people, especially young people of color – not just the musicians themselves, but a whole cottage industry of lawyers like Kervin, accountants, small label executives, managers, and many, many more. “Early hip hop placed a strong emphasis on self determination, and many young Black lawyers got their start thanks to this industry.” Those opportunities extended to Kervin himself. He “began representing a couple of young film documentarians, and from there I started doing a lot more. Most of my friends were musicians and writers (ex: Greg Tate, Peter Lord, Gary Harris, Curtis Lundy), and wanted me to help out.” It wasn’t easy, and Kervin traveled all over, not only NYC, but the whole country to develop his skill set to represent creatives. He focuses on contracts, transactions, and protecting intellectual property of both emerging and established artists. “I’ve always had a fascination with the arts, ever since I was a kid,” he recalls, “music, films, and a good book were the light force that kept me motivated”.

“My clients would come to meet me, and they would get here early just to spend time at the pizza shop at 8th and Broadway or the corner of the Houston and Broadway and be part of it all on the street.” Kervin fondly remembers the hangout that was that corner, with all the shoe shops, the good social vibe of it, the people sauntering in the latest fashion, and the amazingly communal vibe. “Everybody here felt like they were something special,” and everyone had a story, it didn’t matter how famous you were, people gave you space and treated you as an individual with something to offer. It was always bubbling with activity. Though many of the recording studios, producers, and record labels have moved out, their impact on NoHo remains important to the neighborhood, especially in regards to street art and fashion. Even thirty years later, people still return to storied spots and legendary walls to pay homage to some of the original graffiti artists like Basquiat and Al Diaz who made their mark right here in the neighborhood. Fashion-wise, the rise of sneaker culture and streetwear is directly related to hip hop’s rise in NoHo. Brands like Supreme started on Lafayette Street with their own unique sense of style and were an instant hit with the hip hop scene. Most notable in NoHo is still KITH, which grew out of NoHo’s beloved Atrium. Even though the hip hop scene is less pronounced in NoHo now, young musicians and artists still come to the neighborhood to take part in the scene that grew out of the Golden Age of Hip Hop in our special slice of New York City.

Even after all these years, it’s never felt like a big effort or a tough job for Kervin to be here in NoHo doing the work he does. He remembers spending basically every waking moment either at the office, out with a client, or walking up and down the NoHo streets and taking in the sights and sounds of Broadway and Lafayette. Kervin still finds himself continually drawn to the unique vibrancy that Lower Manhattan, and especially NoHo, offers. “I’m here until my eyes close, and after that I’ll be haunting the streets here,” he declares with a chuckle. Though a lot of the initial scene that drew him to NoHo is no longer here, there really is nowhere but NoHo he’d rather be. Kervin’s always “believed in the power of a good book, song, or film to take you places.” Luckily for us, art and music took Kervin right here to NoHo thirty years ago, and he’s helped the neighborhood remain a vibrant, one-of-a-kind creative community ever since.